The Detail hosted its first conference, along with the Social Change Initiative, around the anniversary of the agreement referendum on May 22, 1998.

Around 71% of those who voted in the referendum backed the Good Friday deal.

However, activists from a wide range of sectors warned that some of the commitments made in the agreement still have not been enacted.

Martin O'Brien, director of the Social Change Initiative, said although the agreement has brought about relative peace, there is still much work to be done to tackle poverty and inequality across Northern Ireland.

He said a Northern Ireland Bill of Rights still needs to be established, particularly in light of Brexit and the British government's controversial legacy bill which offers a conditional amnesty to those accused of Troubles-related killings and other crimes.

"You can't afford to stop because power does regroup," he said.

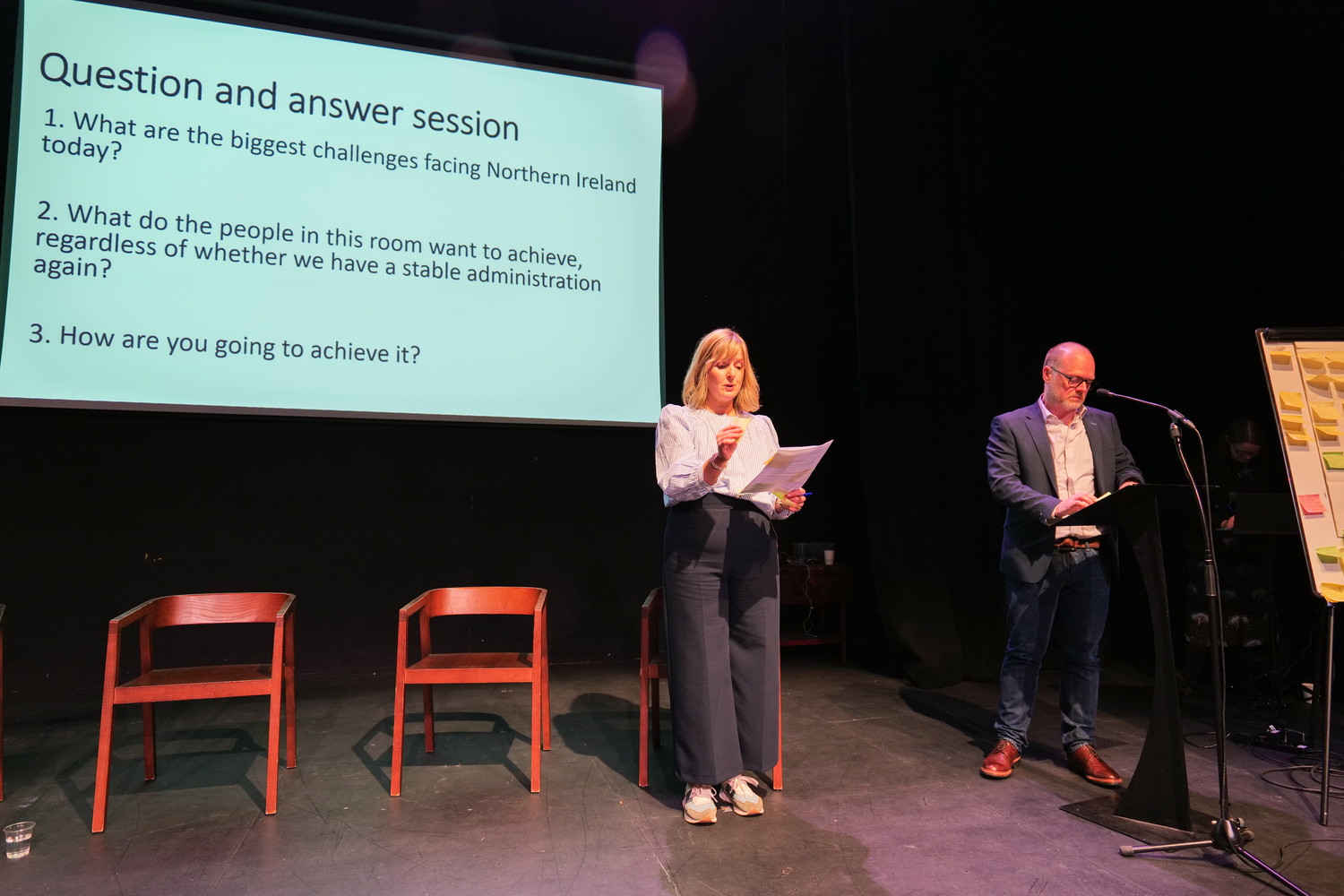

The half-day conference saw scores of activists from across Northern Ireland come together in Belfast to discuss a variety of campaigns and approaches.

The event included three discussion panels and a lively question and answer session.

(L-R) Patricia McKeown from UNISON, Martin O'Brien from SCI and Avila Kilmurray, formerly of the Women's Coalition. Picture by Chris Scott, The Detail

Mr O’Brien spoke as part of a panel on the role of civic society in influencing the agreement.

As director of the Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) at the time of the agreement, he worked along with others to “try to ensure that issues of justice and fairness were included in the agreement”.

Avila Kilmurray, a founder member of the Women’s Coalition, said that during the agreement negotiations party members emphasised “values and principles”.

“The Women’s Coalition was based on three values: inclusion… equality and human rights,” she said.

Patricia McKeown, regional secretary at UNISON, said the members of her union were also keen to see “equality and rights dimensions” in the agreement.

She said at the time there was “no real dialogue between the people and those who were making decisions behind closed doors”.

“That’s something we hoped would be remedied after the agreement and that 25 years later we would have a real relationship with the people we elect but that hasn’t come to pass yet,” she said.

Conchúr Ó Muadaigh from Conradh na Gaeilge, former Green Party leader Clare Bailey and Seán Brady from PPR. Photo by Chris Scott, The Detail

During a panel discussion on post-Good Friday Agreement campaigns, Conchúr Ó Muadaigh from all-Ireland Irish language body Conradh na Gaeilge said the fight for language legislation was successful because it was rooted in community activism.

“The agreement was important, it was significant but we always knew we had that connection with the history of where we came from,” he said.

Former Green Party leader Clare Bailey, who led the campaign for Northern Ireland’s first climate legislation, said although the agreement had not directly addressed climate issues, it did “create a political space for these debates and that level of engagement”.

Seán Brady from Participation and the Practice of Rights (PPR), who has led several successful housing campaigns, said segregated public housing in the north still needs to be addressed.

But he said he is heartened by how people directly affected by housing issues are “more and more holding institutions to account”.

During a panel on the future of activism, James Orr, director of Friends of the Earth Northern Ireland, said activists are increasingly highlighting links between key campaigns.

“We’re seeing ourselves as part of an international community… the refugee narrative, the rise of the far right and a lot of the unsavoury things that we’re seeing in the news over the last few weeks that’s the shape of things to come,” he said.

“This is about climate refugees already happening. Environmentalists need to stop being environmentalists, we all need to start being human beings.”

Twasul Mohammed from Anaka Women’s Collective, who works with refugees in the north, said more needs to be done to help migrants integrate into the community.

The packed audience applauded Ms Mohammed, who is originally from Sudan, after she said refugees are suffering due to disparities in how people from different countries are treated by the British government.

“You are seeing planes leaving Sudan (which is in the midst of a civil war) almost empty. Compare that with (the treatment of) Ukrainian refugees,” she said.

(L-R) James Orr from Friends of the Earth, Twasul Mohammed from Anaka Women's Collective, Dessie Donnelly from Rabble Co-operative, Jackie Redpath from Greater Shankill Partnership. Picture by Chris Scott, The Detail

Jackie Redpath, from the Greater Shankill Partnership, has campaigned for years to improve educational underachievement amongst Protestant working-class boys.

He told the audience that change often takes much longer than anticipated.

“This is generational and it will take a generation to change but it is happening,” he said.

He added that although exam results are improving, the campaign has needed a “whole community effort and resources” including support from parents.

Dessie Donnelly from Rabble Co-operative, which uses digital tools to help activists, said some of the most exciting campaigns are coming from groups which are open to a variety of approaches.

“There isn’t that automatic reflex of ‘what do we do when we have a problem, well we lobby the politicians and committees’... that’ll go on months and months,” he said.

He cited a campaign to reinstate money for Irish language education which saw children affected by cuts protest at the Education Authority building in Belfast.

“That made the difference,” he said.

“This was about a social movement which wasn’t just about NGOs (non-governmental organisations) and the professionalisation of activism but it existed within a community."

By

By