Martin McDonagh is setting up a Traveller-led group in Omagh to tackle discrimination. Photo by Chris Scott, The Detail

“It's not ‘what pub would you like to go to?’... It’s always ‘Where will we actually get in the door?’”. In the second in a series of articles about issues facing the Irish Traveller community, Luke Butterly speaks to Traveller activists about their experiences of discrimination.

===

When Martin McDonagh wanted to go to a restaurant to celebrate his parents’ wedding anniversary, he struggled to find somewhere which would accept his booking.

The 37-year-old, from Omagh, Co Tyrone, said one restaurant told him the premises were full - but only after he gave his name.

“In the likes of Omagh, there tend to be Traveller surnames that dominate. In Omagh, it tends to be McDonagh or Ward,” he said.

“And as soon as they hear your surname - ‘no, we are not serving’. Which is horrible.”

Travellers have been recognised as an ethnic minority in Northern Ireland since 1997 and discrimination on those grounds is illegal.

But Mr McDonagh said Travellers are still being refused service in hotels and pubs due to their background.

“It’s not ‘what pub would you like to go to?’, or ‘I hear so-and-so has music on tonight’,” he said.

“It’s always ‘Where will we actually get in the door?’.”

Large family gatherings are particularly difficult, he said.

“The big moments like christenings, weddings, holy communions, they are massive events for families to get together. And venues are nearly impossible to get,” he said.

“There are usually one or two hotels that are - it’s a horrible way to phrase it - friendly to Travellers.”

Mr McDonagh’s experiences have prompted him to begin setting up a Traveller support group, led by Travellers, in Omagh.

He is also studying for a masters in law at Ulster University.

“I've always been attracted to law because I can see the power that it can do for helping vulnerable and marginalised communities,” he said.

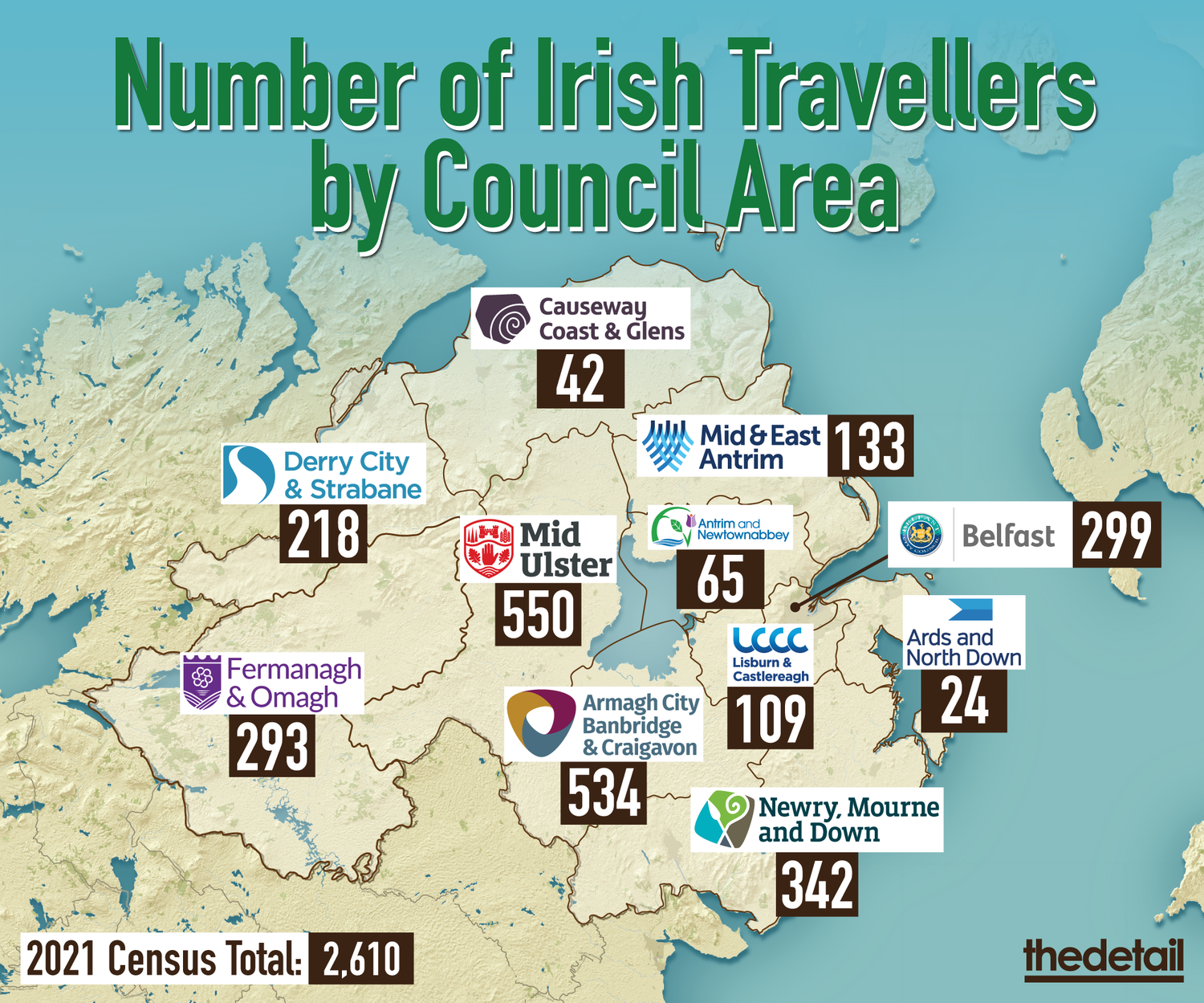

According to 2021 Census figures, the number of Travellers living in Northern Ireland has doubled in the last decade - from 1,301 in 2011 to 2,610 in 2021.

Around a quarter - 674 people - live in Omagh.

Mr McDonagh’s new group, which is still being established and does not yet have a name, aims to tackle anti-Traveller prejudice, first in the Omagh area and later across the whole of Northern Ireland.

His first steps will include talking to businesses about issues Travellers face.

“I think it's best if you get everyone on board, explain the issues, hear what they have to say,” he said.

“Get the message out that it is unacceptable to just bar everyone from an ethnic group for the actions of a minority.

“No one's looking for special treatment, just equal treatment.”

Prejudice against Travellers is still prevalent in the north.

In 2007, the Northern Ireland Life & Times Survey found 53% of respondents said they would not “willingly accept” an Irish Traveller as a neighbour; 47% would not accept a Traveller as a relative through marriage and 45% would not accept a Traveller as a close friend.

By 2022, those figures had reduced but still around a third of respondents (32%) said they would not “willingly accept” a Traveller as a neighbour or a relative through marriage. And 31% said they would not accept a Traveller as a close friend.

Mr McDonagh said prejudice has impacted Travellers’ mental health.

“Everyone knows someone who has died from suicide,” he said.

“And if you can drive that message that these actions (prejudice) are actually having consequences, people might think twice about what they're doing.”

Traveller support groups

Northern Ireland has three independent Traveller support groups: the Craigavon Travellers Support Committee; Armagh Roma and Traveller Support, and An Tearmann in Coalisland, Co Tyrone. Other organisations, including South Tyrone Empowerment Programme (STEP) in Dungannon, Co Tyrone, also run projects to support Travellers.

However, Travellers and activists have told The Detail that, unlike the Republic of Ireland or Britain, no group is led by Travellers.

Pavee Point and the Irish Traveller Movement (ITM) in the Republic have been operating since 1985 and 1990 respectively. In Britain, the Traveller Movement in Britain has provided support since 1999.

Mr McDonagh praised the work of some support groups but said it is important that Travellers represent themselves.

“You also run the risk - and there have been cases - of organisations that are speaking for Travellers that aren't actually engaging with Travellers,” he said.

“They're speaking for them, rather than with them.”

Amy Ward has been active in Traveller groups in Northern Ireland and now works for the Dublin-based ITM.

While some groups supporting Travellers in the north have Traveller staff, she said “there have been none that are actually led”.

“As in, none that are Traveller organisations, none that have a strategy set by Travellers, are actually run by us,” she said.

“There is a massive difference and herein lies the problem.”

She said the reasons for a dearth of Traveller-led groups in the north are complicated but are partly due to fewer Travellers living in Northern Ireland.

Census figures show that 32,949 Travellers live in the Republic, compared to 2,610 in the north.

Ms Ward said many Travellers are wary of engaging with statutory organisations and charities.

“Most of the organisations’ work that is funded vis-à-vis Travellers is for crisis work,” she said.

“This informs how such groups and society views Travellers.

“I would have to say certainly across the north, there has been a huge distrust created by this.

“That’s the main issue.”

She said many people who work with Travellers do have “extremely good intentions” but that the community had suffered from “a lot of tokenism, which drives Travellers away from engaging with these organisations”.

She highlighted the work of former MP Bernadette McAliskey, co-founder of STEP, as a positive example.

“Anything about civil rights, she (Ms McAliskey) always brings Travellers into it, which speaks volumes about her intentions,” she said.

Mr McDonagh added that some Travellers feel they do not have the experience or formal education needed to run an organisation.

“A lot of Travellers have literacy issues… especially computer illiteracy,” he said.

“A lot of travellers are actually functionally illiterate. That is one of the hidden impacts (of poor experiences in education).

“So some people who might run an organisation might not have the experience, through no fault of their own.”

The Border

Ms Ward said Travellers do not fit neatly into either the unionist or nationalist community and have struggled to access peace funding aimed at rebuilding Northern Ireland following the Troubles.

“In terms of the legacy of the Troubles, the way that community development has always been taken up by them (representatives from the two main communities),” she said.

“Ourselves were largely excluded. (The) peace funding model was genuinely about the two communities.”

Ms Ward said Travellers have also been hurt by a legacy of prejudice on both sides of the border.

In the Republic, an Irish government Commission on Itinerancy was set up in the 1960s to examine “the problem arising from the presence in the country of itinerants in considerable numbers” and “the economic, educational, health and social problems inherent in their way of life”.

After a report by the commission was published in 1963, the government launched a national programme encouraging Travellers to live in houses and assimilate with the general population.

In Northern Ireland, Stormont established an Itinerant Gypsies Committee, which also recommended that Travellers live in houses. In addition, police were given extra powers to arrest and summarily convict Travellers camping at the side of a road.

Ms Ward said that the border has limited Traveller advocacy.

“To a large extent the Irish Traveller movement stopped at the border, and the ones in Britain have also stopped at the border,” she said.

“And that’s a massive problem.”

This investigation was supported by a grant from the St Stephen’s Green Trust

By

By