NEW figures revealing that more than 40% of police stations on either side of the Irish border have closed since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement have prompted questions over how any new EU/UK border will be policed post-Brexit.

An analysis by The Detail of the number of police stations within a ten mile radius of the border has revealed that 40 police stations have been closed by the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) and An Garda Síochána over the past two decades.

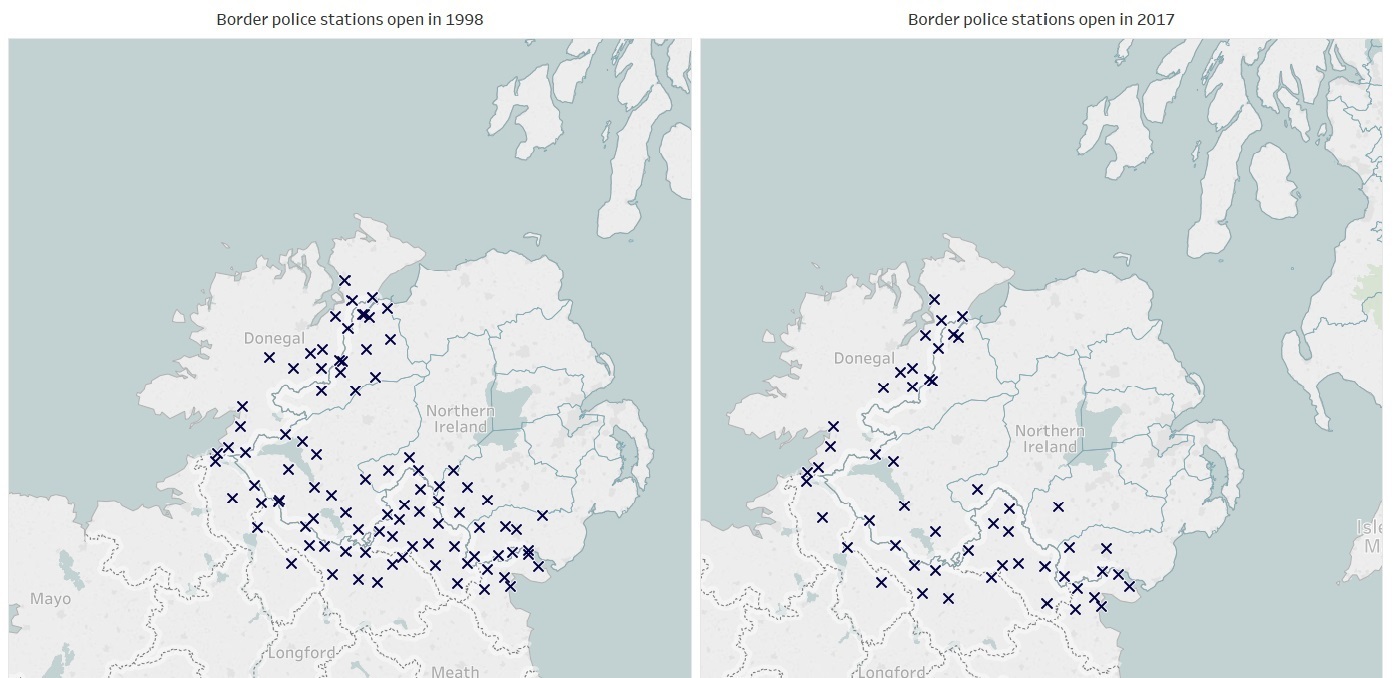

In 1998 there were 92 police stations within a 10 mile radius of the border. Today 52 stations remain operational although the majority are part-time or have limited public opening hours.

A further breakdown reveals significantly more border station closures in the north than the south since the Good Friday Agreement – 28 border stations run by the PSNI or its predecessor the RUC have closed since 1998, compared to 12 Garda stations on the southern side of the border.

Today 11 PSNI stations and 41 Garda stations remain operational within a 10 mile radius of the 300 mile long border which has an estimated 275 crossings.

Source: PSNI/Gardai. The exact location of police stations was available and mapped for stations open in 2017. For stations closed since 1998 the location was unavailable and was determined to be the centre of the relevant town or village.

- Click here to view an interactive version of this graphic.

The figures revealing the loss of a total of 43% of police facilities near the border come as the UK government has insisted there will be no return to the “borders of the past” and that Brexit will not see any physical infrastructure along the border. The UK has, however, been accused of pursuing Brexit policies which will harden the border, with no answers yet as to how that can be avoided.

In the absence of clear solutions and with fewer police stations along the border, however, the figures raise questions over how the potential for increased criminal activity and smuggling across a porous EU/UK border will be addressed post-Brexit.

The Centre for Cross Border Studies, an independent research and policy think-tank focusing on issues related to cross-border cooperation, said Brexit had the potential to bring serious risks and challenges both at and beyond the border but that the complexities and practicalities of policing a new EU/UK border had yet to be fully examined or thought out.

“The border has only been addressed as a high level principle at the Brexit negotiating table but security and other issues, the nitty gritty and the day-to-day practicalities that will directly affect the lives of communities on both sides of the border, that has not been fully examined or explored in any meaningful way to date,” Deputy Director of the Centre for Cross Border Studies Dr Anthony Soares told The Detail.

Police chiefs have confirmed that contingency planning for Brexit and its implications on border policing is in train.

There are concerns among rank and file police officers in the north, however, about current staffing levels and resources.

This comes after concerns were raised over the loss of European Arrest Warrants post-Brexit, which have proven to be vital in combating serious crime, as recently reported by The Detail here.

Pre-Brexit closures

Since the Good Friday Agreement a total of 69 police stations closed across Northern Ireland, 28 of which were located within 10 miles of the border.

Over the same period 139 Garda stations were closed in the republic, 12 of which were located within 10 miles of the border.

Police stations were identified as being within 10 miles of the border as the crow flies.

All of these stations were closed before the Brexit question was even conceived and many were rurally based and had limited opening hours.

Of the 52 border police stations that remain today, the majority operate on a part-time basis or have limited public opening hours.

Our analysis found that none of the 11 border police stations in the north are open to the public on a 24-hour basis; in the south eight of the 41 border stations are open to the public on a 24-hour basis.

The public opening hours of all other stations range from three hours per day to full daytime hours. Stations may be operational but have limited public opening hours.

The PSNI declined to provide details of which stations operate on a 24-hour basis.

PSNI Superintendent Simon Walls told The Detail: “The reality of modern policing is that it is delivered by people and not buildings. We will continue to provide a service that is reflective of the issues and concerns of the local community.

“Policing remains a 24 hours, seven days a week operation and we will continue to be there at people’s time of need and in emergency situations and I would continue to encourage people to contact us if they need to report an incident, at any time of the day or night, on either 101 or on 999 for emergencies.”

New border, new challenges

Brexit negotiations have to date placed significant emphasis on the economics of the border in terms of future trade and customs arrangements.

However, there has been little clarity on how a new UK/EU border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland will be policed in the future.

Proposals published by the UK government in August on how the border might operate in the future focussed on the movement of goods and people but failed to mention specific implications for policing, immigration control, or security.

The exact location of police stations was available and mapped for stations open in 2017. For stations closed since 1998 the location was unavailable and was determined to be the centre of the relevant town or village.

- Click here to view an interactive version of this graphic.

Deputy Director of the Centre for Cross Border Studies Dr Anthony Soares said Brexit brought serious risks and challenges that had yet to be addressed.

“The potential implications are far reaching and go beyond the border. There is the potential for increased criminality and for increased activity by paramilitary organisations on both sides of the border. It’s an underlying indication of what may happen post-Brexit,” Mr Soares told The Detail.

“However, there has been no real account taken of the complexities of the issues Northern Ireland will have to deal with in terms of Brexit and a new EU border. There has been no real thought given to what the consequences of Brexit will be for people working and living on either side of the border.”

Introducing any new physical infrastructure or re-opening police stations along the border would also bring risks, Mr Soares said.

“If Brexit means reintroducing any infrastructure near or at the border, including police stations, they will become a potential target for attacks,” he said.

“To reopen police stations would also have a psychological affect on border communities and reinforce psychologically the presence of the border and that would be a backward step,” he added.

Cross border co-operation

The reality that the existing border is exploited for criminal gain is not lost on the PSNI and Gardaí.

The smuggling of contraband and people across the border, excise fraud, cybercrime, illegal dumping, money laundering, and rural crime were just some of the threats identified by both forces last year.

A joint threat assessment of organised crime, published in September 2016, also identified the abuse of the Common Travel Area as a “current threat”.

The Common Travel Area, the biennial report noted, “could be open to exploitation by criminals, illegal immigrants and extremists who use the border to facilitate and enable criminality.”

In a joint cross border policing strategy, also published in September 2016, the PSNI and Gardaí further highlighted the need for continued co-operation on issues like intelligence sharing, emergency planning, community relations, and rural policing but without broaching the subject of Brexit.

A year on, however, police chiefs have signalled that “scenario planning” for Brexit is in train.

In recent weeks PSNI Chief Constable George Hamilton also confirmed that a joint report would be ready before the end of the year.

“We have commissioned a piece of work that is running parallel to other work going on in the sort of policy and government space but this is police to police, identifying the consequences and the implications of Brexit,” PSNI Chief Constable George Hamilton told the NI Affairs Parliamentary Committee in October.

“We’re hoping that from an operational perspective that it will be a stimulus for some sort of agreement in this justice and security space,” he added.

The prospect of a hard border would be a concern, he said: “There are very practical operational policing consequences for a hard border. We know that a hard border would be exploited by organised criminality and, more worryingly, by violent dissident republican groupings because inevitably it would need to have some manifestation of the state at the border, probably in terms of people but even in terms of technology. Those people and technology would need to be protected and that brings probably police officers into that arena, they in turn then become a target”.

The PSNI chief constable added: “What we would prefer is to have the resources and the agility to police that (the border) from an immigration, from an organised crime, from a terrorist perspective in a much more agile and unpredictable way because we think it’s more effective.”

Policing concerns

The Garda Representative Association (GRA), which represents over 10,000 police officers in the south, declined to comment on the possible implications of Brexit and how the border may be policed in the future as it was an “operational matter”.

But rank and file police officers in Northern Ireland are concerned over what Brexit might mean and whether the PSNI is adequately resourced to deal with potential risks and challenges posed by a new EU/UK border.

The Police Federation of Northern Ireland said the decline in the number of officers was of greater concern than the number of border police stations.

Police Federation Chair Mark Lindsay said year-on-year budget cuts of more than £250 million since 2011 and further cuts of £20 million in the next year in addition to falling officer numbers were proving detrimental to the PSNI and the communities it served.

“The number of police stations along the border isn’t of significant concern in terms of being able to put boots on the ground. What is worrying, however, is a fall in the number of police officers and that is a real concern on a day to day basis for policing across Northern Ireland,” Mr Lindsay said.

The Federation Chair said the strength of the force fell short of the almost 7,000 member threshold accepted by police management in 2014 or the 7,500 officers recommended in the Patten Report.

“There’s not near enough staff in place to meet current policing demands let alone deal with a new European frontier after Brexit. We’re currently at less than 6,700 police officers across Northern Ireland and we’re seeing members leaving the force at a rate of around 30 per month. And this is without any Brexit issues to deal with,” Mr Lindsay said.

Brexit, Mr Lindsay said, will bring challenges and risks, regardless of the type of border that emerges.

“If you’re looking at a pathway for organised crime, such as smuggling goods or people, that’s the real risk that could be posed for the border after Brexit.

“No matter whether there is a hard or a soft border there is going to be a policing requirement and that will mean the need for additional resources.”

The Police Federation Chair added: “Even if there is some form of electronic border there will still be a need for bodies on the ground to enforce what the technology is saying.”

By

By