Health Minister Robin Swann, First Minister Arlene Foster, deputy First Minister Michelle ONeill and Finance Minister Conor Murphy. Photo by Jonathan Porter, Press Eye.

THE top line results of The Detail/LucidTalk's comprehensive polling suggest that the appetite for a united Ireland amongst Northern Irish voters is almost evenly divided.

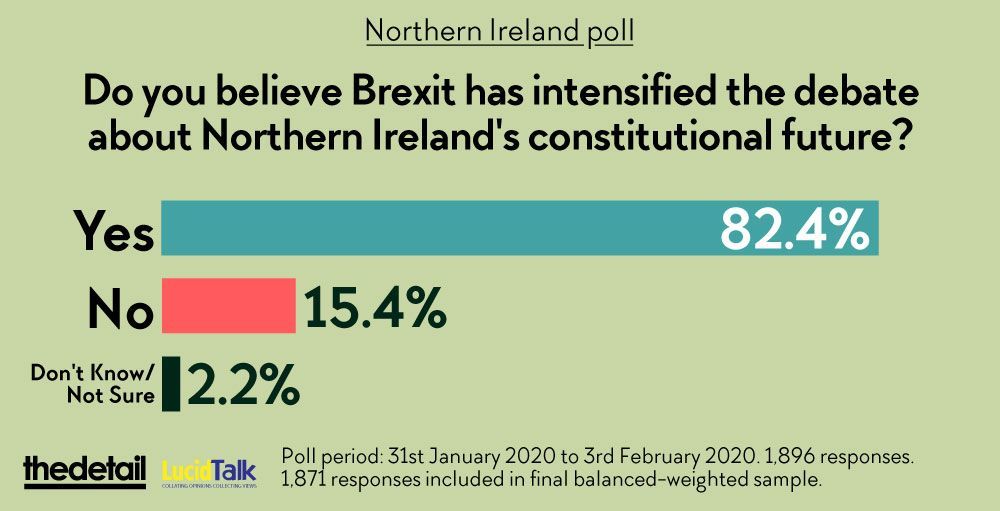

The split comes as no surprise as the politics of Northern Ireland has become increasingly polarised since the Brexit referendum took place in 2016.

Since 2016, the delicate political and constitutional balance which the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 had achieved has been under pressure, with political opportunism of both the main republican and unionist parties amplifying differences and undermining trust between both sides.

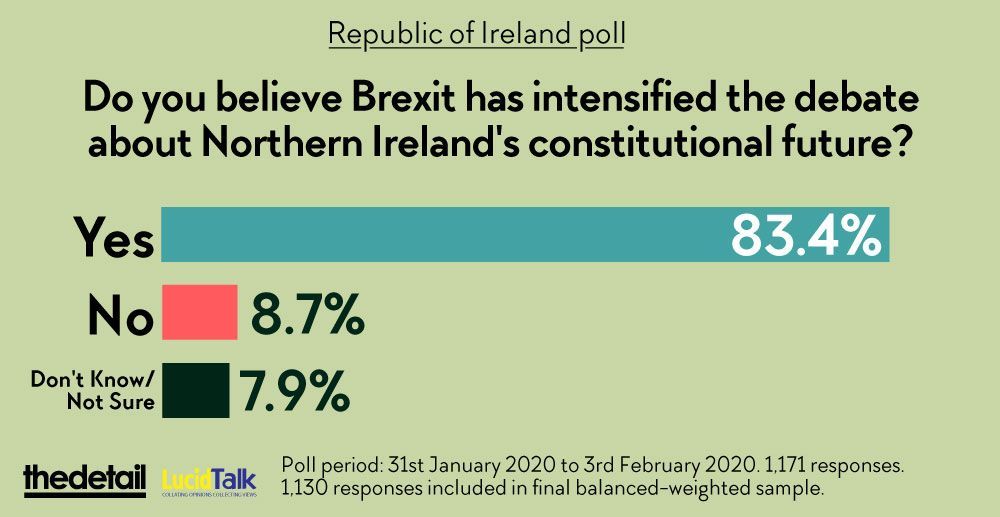

There is no doubt that Brexit divides opinion in Northern Ireland, unlike in the south, where the overwhelming majority of people are deeply unhappy about the UK decision to leave the European Union.

This chasm on the subject of Brexit has been easily exploited since the referendum, with Sinn Féin in particular repeatedly calling for a border poll and seeing Brexit as a tool to push its agenda for Irish reunification.

At the same time, the DUP has used its position in Westminster over the past few years in an effort to cement Northern Ireland’s relationship with London as a hard Brexit looked increasingly probable.

Both parties have played to the fears and emotions of their bases, and Brexit has clearly enabled them to do this. It is a divisive issue which has provided plenty of ammunition for republicans and unionists alike.

Now that the Article 50 process has concluded and the nature of the UK’s departure is somewhat clear (although there is a long way to go in terms of real clarity) the impact of the past few years will begin to crystallise. Political developments in the south will also have a bearing on this.

The trenchant opposition of Sinn Féin to Brexit and the ardent support of the DUP has alienated core constituencies from both communities, but particularly amongst unionists.

For many, the DUP support for Brexit was not reflective of the desire of many unionists to remain in the European Union and maintain the existing constitutional order.

This is clear from the fact that 55.8% of voters opted to remain in 2016. If anything support to remain in the EU has strengthened since then and the poll bears this out, with 68.7% of NI voters unhappy with the Brexit deal.

The dynamics around northern politics over the past few years, along with developments in the recent Dáil elections will inevitably intensify the discourse around the likelihood of a united Ireland in the months and years to come.

The shock result in the general election on February 8th, which saw Sinn Féin emerge as the party with the largest share of votes in the south, will force the subject of a united Ireland onto the political agenda, whether the other parties in the south want it or not.

Sinn Féin’s self-confidence is at an all time high and the party believes it has a strong hand to demand that a potential border poll be held in the near future.

Any negotiations around the formation of a potential government involving Sinn Féin will inevitably involve a discussion of this sort. Recent statements from the party suggest they want a new special unit to be created in the Department of an Taoiseach specifically dealing with preparations for such a poll, with a Minister of State position created to oversee this planning.

While some of this is posturing, there is no doubt that Sinn Féin will continue to push the agenda whether in government or opposition in the south.

In truth, Brexit had pushed this discussion up the political agenda in the south in any event. Controversially, Tánaiste Simon Coveney expressed his desire to see Irish reunification taking place “in my lifetime” shortly after he assumed his position.

While this statement was considered to be somewhat incendiary amongst northern unionists coming from such a senior figure in the Irish Government, and was not subsequently repeated by the Tánaiste, it does show that the Irish Government was thinking afresh about the subject for the first time since 1998.

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar has also made several statements about the inevitability of a united Ireland, but without being prescriptive in relation to a timeframe.

His remarks have usually been offered in response to media queries, themselves indicative of an intensified public debate about the future of the north, which has taken off since 2016.

Outside of politics, Brexit has inspired other stakeholders to start looking more deeply at the questions surrounding the relationship between Northern Ireland and the Republic.

Business organisations have begun to place far greater emphasis on the future of the all island economy – seeking solutions to potential supply chain disruption posed by Brexit, but also looking at the opportunities that arise from a cohesive, economically integrated island.

Universities have also begun to examine the political and constitutional challenges that arise in the context of an intensified focus on a united Ireland.

Academics from Trinity College Dublin, Queen's University Belfast and University College London are all engaged in analysis of potential economic, political and constitutional implications of a united Ireland.

They have understood that a movement towards a referendum on both sides of the border has intensified and see a need for many of the complex issues associated with such a poll to be teased out.

Momentum towards an eventual united Ireland, arising from the 2016 referendum, is unlikely to be quelled in the near time, given that a disruptive Brexit looks to be firmly on the cards.

The likelihood of a threadbare free trade agreement (FTA) between the EU and the UK is intensifying, and will have major implications for the economic wellbeing of Northern Ireland and east-west trade between the island of Ireland and Great Britain.

That is if any trade deal can be agreed and increasingly it seems that the British Government is moving to a scenario whereby no FTA will be struck, but rather the UK would move to trading with the EU on the basis of world trade organisation rules.

Such an outcome would be enormously disruptive for Northern Ireland and would dramatically intensify political pressure for a border poll.

Other factors will play a role in the coming months and years. If Scotland was to initiate another independence referendum, the demand for a poll in Northern Ireland would be very difficult to resist.

This, coupled with an unsatisfactory outcome in EU/UK FTA negotiations and the rise of Sinn Féin in southern politics could provide the perfect conditions for an uncontainable groundswell of momentum for a border poll.

One thing is clear, irrespective of who will be in government south of the border, the prudent course of action will be to initiate slow, deliberative and inclusive preparations for a potential referendum at some point in the future.

A united Ireland would have to be one which respects and celebrates all of the traditions, religions and cultures on the island.

It could only succeed if it was genuinely united – not just in terms of geography but in terms of people.

The breakdown of the Northern Ireland Executive and the political stalemate which ensued for two and a half years tells us a lot about how mature and ready for such a move the political leaders of Northern Ireland are.

Likewise, the reaction of some Sinn Féin TDs to their recent election success, by shouting IRA slogans and glorifying the party’s past links with terrorism, show that we have a long way to go.

Notwithstanding posturing and these displays of crass political immaturity, it would be churlish to pretend that political unification of the island will not be on the cards in the future.

It is thus advisable to begin preparations now, so that when the day comes, the people and the institutions will be equipped to adapt and embrace the change.

Such preparations will take years if not decades, but the work should begin now.

- Lucinda Creighton served as Minister for European Affairs in the Fine Gael government from March 2011 to July 2013. She is founder and CEO of Vulcan Consulting Ltd and was a founder member of Renua.