A GOVERNMENT commitment to “reduce, and remove, all interface barriers” in Northern Ireland by 2023 has been called into question after it emerged nearly one in five of the 116 structures are not included in the plan.

The pledge to remove so-called peace walls between unionist and nationalist communities was part of the May 2013 Together Building a United Community (T:BUC) strategy which “reflects the Executive’s commitment to improving community relations and continuing the journey towards a more united and shared society."

T:BUC was agreed by Sinn Fein and the DUP in the aftermath of street protests and violence that erupted following the December 2012 decision to restrict the flying of the Union flag over Belfast City Hall.

Its publication came a month before a visit by the then US President Barack Obama who told an audience at Belfast’s Waterfront Hall that successfully removing the peacewalls, “more than anything, will shape what Northern Ireland looks like 15 years from now and beyond."

But despite the T:BUC pledge to remove "all interface barriers", experts predict the majority are likely to remain in place beyond 2023, while new data shows 21 structures are not even included in the Stormont target.

The peace walls were erected between communities during the Troubles to reduce violence in areas that suffered sustained conflict with many living in their vicinity fearful of any proposed removal.

Four years after T:BUC, Detail Data asked The Executive Office (TEO) for an update on the interface removal project.

A response said: "The exact number of interface barriers is subject to differing views as a result of varying approaches to counting and categorising barriers.

"Progress has been made but this isn't simply a numbers game, where we take down a wall and move on.

“Through our Together Building a United Community strategy, we are committed to reduce and remove all interface barriers by 2023. Reconciliation has been hampered by physical divisions so to help build a truly shared, united and reconciled community, we will work with the local community to remove these structures.”

When pressed for further information on which structures were being targeted, TEO referred Detail Data to the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Housing Executive (NIHE).

DOJ said: “In the context of the Executive’s commitment around the removal of interface structures by 2023, a cross departmental programme board was established by the DOJ to take this work forward and that board agreed that these DOJ structures, along with structures which are the responsibility of the NI Housing Executive, would fall under its remit.”

Freedom of Information requests to both DOJ and NIHE confirmed that this relates to some 74 structures.

However, a new report by the Belfast Interface Project (BIP), which will be published in the coming days, identifies 116 defensive walls, fences, gates and buffers located in Belfast, Derry-Londonderry, Lurgan and Portadown. Research for the project was conducted by Neil Jarman of the Senator George J Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice.

In the BIP report the DOJ/NIHE figure of 74 interface structures is said to be made up of 95 individual separate components.

This, in part, is due to differences in how structures are identified and catalogued, with some ranging from walls stretching hundreds of metres to large planters and gates, or where barriers are made up of intermittent sections of wall or fence which could be counted as a single peace wall or as multiple structures.

More information on the variety of what makes up peace walls can be read here.

Analysis of the BIP data confirms that despite the T:BUC pledge to remove "all interface barriers", some 21 structures will remain in place even if the Stormont target is achieved.

These outstanding structures are controlled by organisations including Belfast City Council (2), Invest NI (2), Belfast HSC Trust (1), The Department for Infrastructure/DRD (3), private (5) and unknown owners (8).

Detail Data asked The Executive Office how the T:BUC commitment to remove all barriers by 2023 could be met, given such omissions. However, a response did not address the issue.

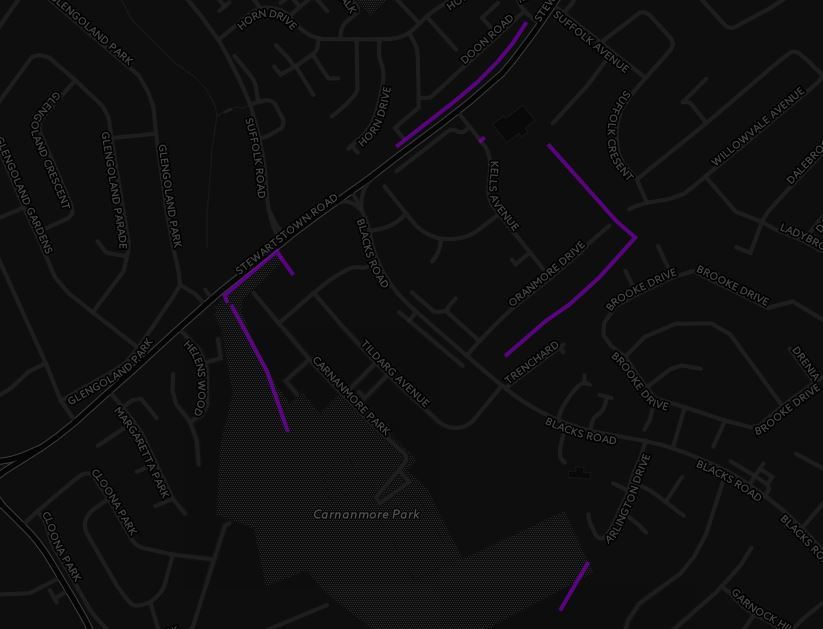

Information on peace walls in place across Northern Ireland is available to explore in the interactive map below, which has been produced by Detail Data’s Bob Harper for the Belfast Interface Project.

The new map shows 16 clusters of barriers around communities as well as information on their composition and age and includes an option to view which barriers will still be in place even if all of those structures now on the Stormont list are removed by 2023.

This follows a recent project by The Detail which mapped 40 years of data to show how Catholic and Protestant communities largely still live apart across Northern Ireland, not just in areas where peace walls exist.

A full screen version of this map can be explored here.

MOVING BEYOND THE WALLS

Despite government assurances that "we are committed to reduce and remove all interface barriers by 2023", Belfast Interface Project (BIP) director Joe O’Donnell does not believe that many of the barriers can or will be removed in such a short timeframe.

“I do not see the wall that runs between the Shankill and Falls being removed in six years," he said.

“I don’t think it is particularly important if we miss the target date of 2023. I’m not sure now in 2017 that anyone considers that we are going to hit that target.”

According to the Housing Executive’s head of community cohesion Jennifer Hawthorne, although progress is being made, it is unlikely all of the structures that remain part of the 2023 target will be removed.

“There is only 1% of the population of the city that live near a peace wall and if you extrapolate that out across Northern Ireland, the percentage of the overall population living beside a peace wall is miniscule – but we expect those communities to take the steps towards peace, to do all the heavy lifting and take all the risks for the benefit of wider society,” she said.

“Once people are able to breach a wall with a pedestrian gate and maybe later a vehicle gate as a community becomes more confident then incrementally maybe it could come down.

"So 2023, yes all walls might not be removed but they could have changed quite a bit.”

Suffolk Lenadoon Interface Group (SLIG), which is made up Suffolk Community Forum and Lenadoon Community Forum, was founded in 1996 to find community based solutions to social justice, equality, regeneration and conflict transformation issues.

Roisin Erskine of Suffolk Community Forum, on the Protestant/unionist side of the interface, said there is little prospect of the barriers that surround the area coming down in the next six years.

"I think everybody is well aware that the communities aren't so bought in to it," she said.

"Our experience in Suffolk is that people are reluctant to even have the conversations because they feel that by their very engagement they are supporting the removal of peace walls.

"Residents in Suffolk are very fearful of the peace walls being taken down.

"However, if we are working to Stormont deadlines then 2023 could actually be 2033 so I wouldn’t be getting too animated or excited about it being a deadline anyway."

Renee Crawford of Lenadoon Community Forum, on the Catholic/nationalist side of the interface, agrees and believes that the loss of funding for interface related projects will only make aspirations for removal more difficult.

“I know that the feeling when that came out was that people were kind of horrified," she said.

“There was a feeling of fear – particularly if you lived in the smaller community that someone would come in and say ‘Right, in 2023 all of this is gone’. This is what people have grown up with. This is their protection.

"It took generations to create them and I believe that it is going to take generations to turn that around.

“Some people will never want the walls to go. Some might if they felt safe and secure – some sort of environmental enhancement to it and that is legitimate. But to say that by 2023 they would all be gone? No.

“To hear that groups like SLIG are losing funding because of the current situation [regarding the colllapse of the Stormont government] - if you lose the infrastructure that we have created between the two communities, what happens then?”

The Community Relations Council (CRC) - which administers government grants including many of those used to deliver interface projects – confirmed that uncertainty over Stormont budgets has put some groups on notice.

"There are a number of organisations working in interface areas that whether we are able to fund them depends on the amount of money we have available to us," a CRC spokesperson said.

PROGRESS

Ulster University Criminology lecturer Dr Jonny Byrne, whose work has focussed heavily on interfaces, believes that although the 2023 target is unlikely to be met, huge advances have been made.

“I’ve been working on this since 2002 and did my PHD on it in 2008,” he said.

“Back then you couldn’t say to people ‘how are we going to take this wall down?’ If you had done that people would have turned off the recorder and walked out of the room.

“That is community, politicians – they weren’t talking about that. So to go from that in 2008 to saying they would take the walls down in 2013 is incredible.

“I understand completely the need to have a definitive figure so that we can benchmark success and monitor progress. But we have the headline policy and what we have done badly is communicate is what that means in real terms.”

In terms of barrier removals and reductions delivered since T:BUC, DOJ said that it has removed five sets of gates in Derry/Londonderry; fencing from Torrens Crescent (Belfast) and Longlands Road (Newtownabbey); barriers at Brucevale Park, Newington Street and Arthur's Bridge (all Belfast).

DOJ added that it has also conducted partial removals of fencing at Belfast's Moyard Parade, Duncairn/North Queen Street as well as the partial removal of gates at Springmartin Road and at Derry/Londonderry’s historic walls.

For its part, the Housing Executive highlighted reimaging and environmental improvement works that it has conducted at a number of its interface locations since T:BUC. These include environmental planting and new housing at Mountainview Parade/Somerdale (north) Belfast and the replacing of palisade fencing with green fencing along the Colin Glen River in Suffolk-Lenadoon.

The Housing Executive also highlighted how low metal fencing and high walls along the Doon Road housing development on the Stewartstown Road in west Belfast (along of the Suffolk-Lenadoon interface) are being reimaged by the city’s new Rapid Transit System (BRT).

BRT aims to get cars off the road by providing priority lanes, high quality halts and off-vehicle ticketing in specially designed buses running from west to east Belfast.

According to Renee Crawford, this process required contractors to take concerns and the calendar into consideration.

“I facilitated a steering group for over a year now, with a number of public meetings to let people know what was coming down the line but also to make sure that the contractor was aware for the scheduling of work – that you can’t remove all fencing across July and August at an interface – that you leave people vulnerable and to be minded of that," she said.

“But it has worked out well. The work is nearing completion and any possible trouble relating to that was kept to a minimum.

A Department for Infrastructure map showing a stretch of Belfast's new Rapid Transit service which will run alongside the Stewartstown Road interface.

BRT is expected to launch later this year, but Roisin Erskine believes Suffolk residents will be reluctant to avail of it, despite its proximity.

"Belfast Rapid Transit certainly brings opportunities, but certainly for residents in Suffolk there is a barrier there for people trying to access it," she said.

"Sometimes when things are on your doorstep they aren't necessarily accessible to you."

Belfast Interface Project's new report, will, when published appear here.

To read more about different types of interface, click here.

The data used in this project can be accessed here.

By

By