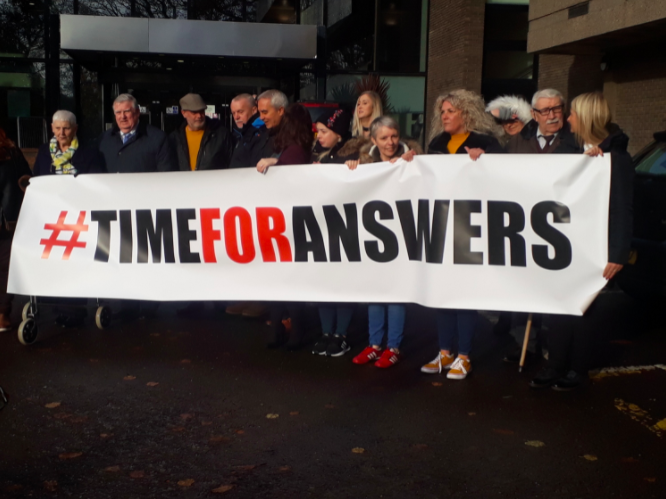

People impacted by the Dr Watt scandal at an earlier protest outside the Department of Health. Photo by Rory Winters.

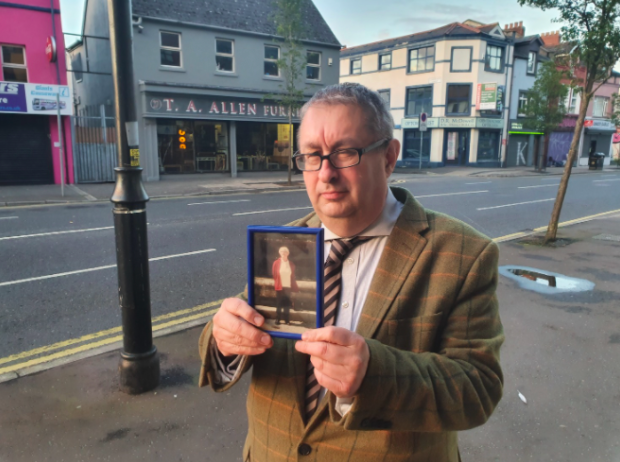

RENOWNED artist George H Smyth has not painted professionally since his wife Rachel, a patient of former Belfast Trust neurologist Dr Michael Watt, died almost five years ago.

Rachel was just 46 when she passed away in January 2018. The couple had been together for 31 years.

During her time under Dr Watt's care, Mr Smyth was worried about the treatment his wife was receiving.

His concerns deepened when in May 2018, just months after Rachel’s death, the Belfast Trust launched the biggest recall of patients in the history of the health service in Northern Ireland.

More than 5,000 of Dr Watt’s former patients were invited to have their cases examined.

Around one in five patients had to have their diagnoses changed.

An independent inquiry and a separate review of the cases of Dr Watt’s deceased patients, including Rachel’s, were also launched in May 2018.

Earlier this year, the public inquiry, chaired by barrister Brett Lockhart KC, revealed "numerous failures" relating to the Dr Watt scandal.

It found that patients had been let down, opportunities were missed by the Belfast Trust to identify problems with the neurologist’s practice, and that earlier intervention by the trust would have made a difference.

In October last year, Dr Watt was removed from the medical register after he made a voluntary application – meaning allegations about his work could not be heard in a General Medical Council (GMC) tribunal.

Review of deceased patients' cases

For the families of some of his deceased patients, many questions remain.

The Department of Health (DoH) commissioned the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority (RQIA) in May 2018 to carry out the review of the cases of deceased patients who had died in the previous ten years.

Around 3,500 of Dr Watt’s patients were estimated to have died in this period.

The RQIA will publish its review tomorrow, but this will only relate to 44 deceased patients.

When asked why thousands of patients had been excluded, an RQIA spokesman said: “The review has been conducted in a phased manner, with the methodology and scope of the approach agreed with the DoH.

He added: "Decisions on any future phases of this review are a matter for the DoH.”

‘Unprofessional, inefficient, hurtful and disappointing’

Following Rachel’s death, Mr Smyth, from Ardglass in Co Down, employed a solicitor to try and get some answers.

Eventually, the solicitor said he did not feel comfortable accepting any more of Mr Smyth’s money because he was getting no information from the RQIA.

Mr Smyth told The Detail the RQIA’s conduct had been “unprofessional, inefficient, hurtful and disappointing” throughout the lengthy review process.

“Over the four-and-a-half years, myself and others have come across so much obfuscation and subterfuge about what’s been happening,” he said.

It is understood the RQIA has privately apologised to some deceased patients’ families for ‘re-traumatising’ them.

The RQIA declined to confirm any apology.

A spokesman said: “Throughout this review, RQIA’s priority has been to place a clear focus on the bereaved families and their deceased relatives.”

Mr Smyth branded the Belfast Trust’s failure to effectively oversee Dr Watt’s neurology practice as “disgraceful, shameful and an absolute travesty”.

And he said attempts to get information from the DoH were futile.

A spokesman from the Belfast Trust told The Detail the trust is “wholly and unreservedly sorry to everyone who has been affected by the neurology recalls since May 2018”.

“Our thoughts today are with the families of those patients who have sadly passed away,” he said.

The DoH declined to comment in advance of the publication of the RQIA report tomorrow.

The PSNI was asked if it is carrying out any investigations into the Dr Watt scandal.

A spokesman said: “Police are currently considering the findings of the various reviews/investigations namely the GMC, the Royal College of Physicians, the RQIA and the Independent Neurology Inquiry.

“We will continue to liaise with the RQIA, DoH and Public Prosecution Service – and will consider all relevant material before determining whether or not it will be necessary to conduct a formal investigation.”

Deceased patients’ records

The RQIA commissioned an expert panel from the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) to assess the records of 44 of Dr Watt's deceased patients.

Tomorrow's RQIA report will summarise the 44 cases.

However, patients’ families have already received individual RCP reports about the care provided to their relatives.

Four people who have received their reports, including Mr Smyth, have shared their stories with The Detail.

They highlight a string of failings including that Dr Watt gave insecure diagnoses to patients, recommended an “apparently unnecessary” neurosurgical procedure and misprescribed drugs.

In one case, a young father who had been a patient of Dr Watt for years died from drug intoxication caused by high levels of prescription medication.

Dr Watt Scandal: A Timeline

- December 2016: A GP raises concerns about Dr Watt's conduct

- July 2017: Dr Watt is restricted from treating patients in the Belfast Trust

- May 2018: The Belfast Trust launches a recall of patients, an independent inquiry is called and a review of deceased patients’ cases is commissioned

- January 2019: Dr Watt is temporarily suspended from practising as a doctor in the UK

- October 2021: Dr Watt is removed from the medical register after he made a voluntary application, meaning he can no longer practise medicine in the UK

- June 2022: The final patient recall report reveals about one in five of Dr Watt’s patients needed to have their diagnoses changed

- June 2022: The public inquiry report reveals failings in the Belfast Trust’s management of Dr Watt

Brett Lockhart KC, speaking at the publication of his public inquiry report. Photo by Kelvin Boyes, Press Eye

‘Exposed to significant risk’

While some of the families feel their loved ones' RCP reports provide clear answers, others have complained that some details are incorrect.

Mr Smyth said: “On the one hand, the RCP report proved me right. It was vindication.

“But on the other hand, seeing it in black and white – the litany of disasters that had occurred – made it more real.”

The report found his wife Rachel had received unsatisfactory care, was given an inaccurate diagnosis, and that Dr Watt “gave the indications for prescription as lupus and MS” despite evidence showing that “the patient had secondary progressive MS”.

Rachel was treated with “powerful immunotherapies” which did not help her condition and “exposed her to significant risk”, the report found.

It stated: “The most straightforward diagnosis was secondary progressive MS. At no point was this considered, according to the documentation.”

If Rachel had been given the correct diagnosis earlier, she “could have planned for a dignified death…free from invasive therapies and investigations”, the report found.

The report also highlighted issues with other unnamed doctors involved in Rachel’s care.

It stated that “the RQIA should consider the potential for harm arising from an inaccurate diagnosis made by several clinicians”, including Dr Watt, “which led to the patient being exposed to unnecessary and potentially dangerous treatments”.

The report also found that the cause of death on Rachel’s death certificate was incorrect and recommended that the RQIA should refer her case to a medical examiner or a coroner.

Mr Smyth said the RQIA assured him on numerous occasions that it had contacted the coroner’s office, but said he later discovered that this had not happened.

He contacted the coroner’s office himself.

“It took me one hour and fifteen minutes to get all the relevant information to the coroner’s office whereas I had been waiting on the RQIA doing it for four months,” Mr Smyth said.

A spokeswoman for the Lady Chief Justice’s office said: “The coroner’s investigation into this case is ongoing and no decision has been reached on inquest.”

‘Our son’s death could have been avoided’

David*, a Co Down father in his early thirties, died in 2006.

His individual RCP report found Dr Watt had prescribed epilepsy medication despite evidence suggesting that David’s seizures were not linked to epilepsy.

“It was not evident that efforts were made to investigate his seizures when there were clear doubts as to the nature of his attacks,” the report found.

Dr Watt recommended surgery to remove a cyst from David’s brain, but the report said this “appeared to be an unnecessary neurosurgical procedure”.

The report also said the team who reviewed David’s case could not “understand why the patient was prescribed high doses of benzodiazepines and narcotics, in addition to high dose medications for epilepsy, when this diagnosis was not secure”.

David’s parents initially trusted Dr Watt, who their son first saw in 1999.

However, they became increasingly concerned about his conduct and decided to get a second opinion in 2006. While he was waiting for his medical files to be sent to the second doctor, David died.

An inquest found David passed away from drug intoxication caused by high levels of prescription medication.

Soon after David’s death, his family raised serious concerns about Dr Watt with the Belfast Trust but said nothing was done.

The report found the trust “appeared somewhat dismissive of these concerns”.

David’s mother *Kerry told The Detail: “It’s dreadful to know that our son’s death in the first place could have been avoided but it’s nearly worse that nothing was learned from it nor action taken.”

She added: “The trust appears to have had little or no effective oversight of Dr Watt.

“There was a failure to monitor his work or conduct annual appraisals.

“We were astounded when on the same day of the issue of the public inquiry report that Cathy Jack (the Belfast Trust chief executive) stated that she wouldn’t be resigning.”

The Detail previously reported how Dr Jack ran a joint clinic with Dr Watt from 2004 until 2007 – during a time when David was being treated by the former neurologist and after he had died.

‘Rowed back on his suspicion’

Belfast woman, Sarah (Ciss) Carabine, was 65 when she was first referred to Dr Watt in August 2015. She died three years later.

Ciss had motor neurone disease (MND) but Dr Watt failed to diagnose her with the condition.

Her individual RCP report found that Dr Watt had initially suspected MND but “rowed back on his suspicion”.

While the RCP said this was “understandable” at that initial stage, it added that Dr Watt “did not actively seek the diagnosis of MND between February 2016 and December 2017”.

It also said Dr Watt “could be criticised for not examining the patient during this time or looking for signs of MND…or documenting clearly that he was doing this”.

The report confirmed that Ciss was only diagnosed with MND when she was admitted to hospital “with another neurologist arranging the tests”.

“The second neurologist…had no difficulty making the diagnosis of MND,” the report stated.

The report also found Dr Watt “was clearly suspicious that the patient might have MND but did not share these suspicions with the patient despite her expressed concerns”.

The RCP initially stated it had no concerns that Dr Watt's treatment had potentially caused Ciss harm.

Orlá Carabine, Ciss’ daughter, told The Detail this seemed “like a complete contradiction” given the report also highlighted “how she was failed”.

When the family formally challenged the RCP's finding, the report was changed to read "in light of the discussions RQIA has held with family members of the deceased patient...there was potential for harm caused in this case”.

Ms Carabine said the family was pleased the finding was changed but said it "shouldn’t have had to come to this".

“The haphazard nature of how our complaint was dealt with, with us only being told this finding would be overturned just before the overall report will be published, is indicative of how poorly the whole process has been handled," she said.

As Ciss was ultimately diagnosed with MND by another doctor, the report found her diagnosis was secure.

The family also challenged this finding, but the RCP did not change it.

“While they have acknowledged Dr Watt’s failure to diagnose my mother with motor neurone disease, despite her concerns that this is what she had, they have maintained the diagnosis was secure," Orlá said.

“However, she didn’t get a diagnosis until six months before she died by another neurologist so we are not at all pleased with that. Dr Watt should not be credited with providing an accurate diagnosis.

“After all this time, I think they have given us the bare minimum.”

‘This is a drug which she should never have had’

Ruth Armstrong was 78 years old when she died in November 2002.

Dr Watt had diagnosed her with focal seizures, which are consistent with epilepsy.

The report found “there were potentially better alternative diagnoses” to epilepsy but there was no evidence that Dr Watt “properly considered these or took sufficient steps to ensure that the diagnosis was as accurate as possible”.

The report questioned why Dr Watt “did not consider syncope (fainting or blackouts)” as the cause of her collapses “despite this being a more likely diagnosis” than seizures caused by epilepsy.

The RCP report found that no MRI scan was carried out, even though the scan is best practice in cases of suspected epilepsy.

“The MRI scan may have shown the presence of a tumour, which was later identified,” the RCP found.

But Ruth Armstrong’s son, Colin, disputed that his mother had a brain tumour.

“It’s highly speculative that there was a tumour in February 2001 as the CT scan at that time did not find neurological problems,” he said.

He said the RCP also took “as fact” that his mother had a brain tumour.

However, experts in England told Mr Armstrong, as late as August 2002, that his mother could have had an abscess rather than a brain tumour.

The report also stated that the anti-epilepsy drug Epanutin, which Dr Watt prescribed to Ruth Armstrong, caused her no harm and that she actually “did well” on this treatment.

However, her son said: “Regardless of any possible side-effects, this is a drug which she should never have had because there was no basis for the diagnosis of epilepsy.”

An academic paper published in 2005 cited a possible connection between Epanutin and tumours.

“The possible impact of that drug should have been examined by a neuropharmacologist as part of this review, but it wasn’t,” Mr Armstrong said.

He also expressed concerns about the extent of the medical evidence which the RCP had access to in compiling his mother’s report.

However, unlike the report on Ciss Carabine – which has been revised as a result of the family’s complaint – the RCP report on Ruth Armstrong was not altered following the concerns her son raised.

The RQIA said: “Unfortunately it is not possible for the RCP to reconvene its expert panel or make further changes to your report.”

Mr Armstrong said the report "isn't good enough".

“There are serious deficiencies in the report into my mother's case," he said.

"I outlined those in the response I sent the RQIA four months ago.”

The Detail approached Dr Watt’s legal team, but no comment was provided by the former neurologist or his representatives.

*David and *Kerry are pseudonyms

By

By