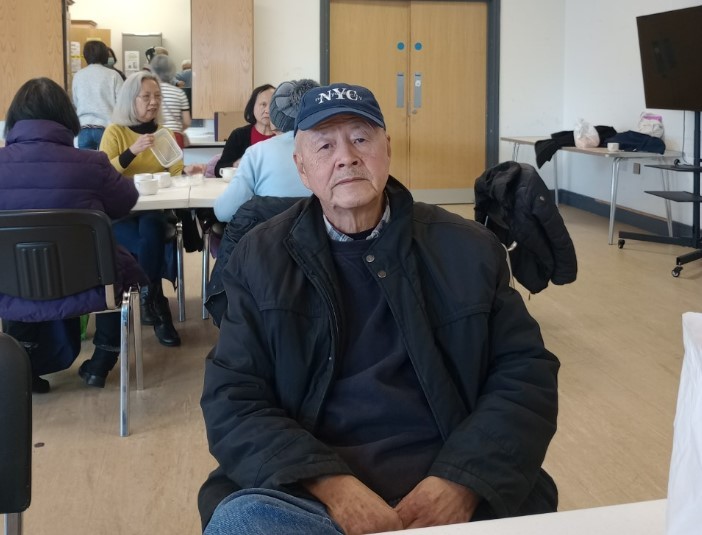

Mr Tam Cheung and Mrs Lam Kiu Cheung at the Chinese Resource Centre in south Belfast. Photo by Luke Butterly, The Detail

Northern Ireland is more diverse than ever. Results from the 2021 Census show that minority ethnic groups account for 3.4% of the population, or 65,600 people. In the first in a series of articles about minorities in the north, Luke Butterly speaks to members of the established Chinese community.

==

WHEN Thomas Ting moved from Hong Kong to Northern Ireland in the 1980s, he was taken aback by the violence of the Troubles.

The martial arts expert, who trained with Hollywood legend Bruce Lee in Hong Kong in the 1960s, clearly remembered the dangers of the conflict.

“Always fighting on the street. You could hear the gunshots,” he said.

“It was very dangerous. You had to take care on the street.”

Known as ‘Sifu’, or Master Ting, he braved the conflict to train more than a thousand people in the north in martial arts.

“I am retired now, because I am an old man,” he said.

“I still have a class, in the Chinese Christian church off the Lisburn Road (in Belfast).”

According to the 2021 census, ethnic minorities make up around 3.4 percent of the north’s population, with people of mixed heritage, Indian and Chinese descent the three largest groups.

Around 9,500 people from a Chinese background live in Northern Ireland - 0.5 percent of the total population.

The figure shows a rise on the 2011 census, which found that around 6,300 people from a Chinese background lived in the north - 0.3 percent of the population.

However, the Chinese Welfare Association estimates that the actual 2021 total is much higher - between 12,000 and 15,000 people - because not all migrants fill out census forms.

Mr Ting is one of a group of Chinese-born migrants who regularly attend events at the Chinese Resource Centre in south Belfast.

A Tuesday lunch club, organised by the Chinese Welfare Association, allows older members of the community to enjoy raffles and a few games of bingo.

Mr Ting said he drives from Bangor in Co Down to the club so his wife can socialise.

“She is retired now, she is very lonely at home. We got married over 60 years ago, nothing to talk about!”

Tommy Lee, who is in his late sixties, has been a member of the group for almost a decade, and was previously a volunteer.

After originally moving to England around 50 years ago, he came to Belfast to work at a small business run by his parents, before opening up his own in Holywood, Co Down.

Mr Lee said he tries to keep things fun and entertaining for the older members of the group.

“We do a lucky draw, and every week it's different prizes. Good fun!”

“Some weeks it's vegetables, sometimes we have eggs, lunch meat. Every week is a different thing, it keeps the old people happy.”

People take turns drawing raffle numbers. On the day The Detail visited, one elderly woman drew her husband’s winning numbers, prompting a chorus of laughter.

“There are usually 30 to 40 people each week,” Mr Lee said.

“Some people just take a day off, others go to a GP checkup, maybe a family day, or go to a different restaurant.”

Some of the people who attend the lunch club are residents of Hong Ling Gardens, a south Belfast retirement home for Chinese people, which opened in 2004.

The 54 bedroom sheltered housing scheme, whose name translates to ‘health and peace’, is home to many of Northern Ireland’s first generation Chinese.

Residents Tam and Lam Kiu Cheung are part of a group of residents who regularly come to the club.

“All our elderly friends come here,” said Mrs Cheung (90).

She said she loves seeing other people.

“Otherwise it's so boring to stay at home. Nothing to do.”

The couple lived in England before moving here in the 1970s. They both worked in the restaurant trade before retiring, and all their children and grandchildren live in Belfast.

“When you are at this age, nothing matters, you just wish there's no pain, no illness. That's all we wish at this age,” she said.

Chinese community in Northern Ireland

The Chinese community is one of the longest-established ethnic minorities in Northern Ireland.

William Olphert, managing director of the Chinese Welfare Association, said there were “just two Chinese people on the census at the foundation of Northern Ireland 100 years ago”.

Large-scale migration began in the 1960s when thousands of workers moved from Hong Kong, then a British colony, to the UK.

Mr Olphert, who is from Ballymoney in Co Antrim but has worked in China and speaks Mandarin, said many of the first migrants were poor farmers from the New Territories area of Hong Kong rather than the more prosperous Hong Kong Island.

In the 1980s, community and business leaders founded the Chinese Welfare Association to help meet the social and health needs of some migrants.

Migration patterns from China to Northern Ireland have changed over the decades.

In recent years, most migrants, ranging from international students, workers and asylum seekers, have come from mainland China.

But in the past year, thousands of people from Hong Kong have moved to the UK under a new visa scheme, partly due to escape tensions with the Chinese authorities.

The Chinese Welfare Association said new migrants from Hong Kong are arriving in Northern Ireland and have contacted the group for help and advice.

In recent years, the association has been involved in cross-community work and has offered its expertise to newer migrants including the Sudanese, Polish and Roma communities.

“Over time we've reached out and have expanded those services to help people who are perhaps in the same place as ourselves 30, 40 years ago,” Mr Olphert said.

Somei Vigo, the association’s Chinese elderly development officer, said many migrants opened businesses when they first arrived in Northern Ireland.

“Someone comes and they open a takeaway, and they bring all the family,” she said.

Ms Vigo said in recent decades, the children or grandchildren of the first migrants have opted to work in other industries rather than family-owned businesses.

‘The whole village’

Ms Vigo, who has been a development officer for 11 years, previously worked for a city councillor in Hong Kong.

She said the funding of support services is a major issue in Northern Ireland.

“Back when I was in Hong Kong, all you had to do was have ideas, and the money is there,” she said.

“Sometimes you get given the money and we are sitting there, saying ok what will we do with that money?”

“Here [in Northern Ireland] though, you have to constantly worry about funding. Even the funding for our job is year by year. There is a lot of uncertainty.”

In 2007, Hong Kong-born Anna Lo became the first politician from an ethnic minority to be elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Ms Lo, who was the UK’s first Chinese parliamentarian, quit politics in 2016. She said racist abuse from loyalists prompted her decision to retire.

Ms Vigo said Ms Lo had strong support from the Chinese community in south Belfast.

But she said that following Ms Lo’s retirement, politicians tend not to engage with the Chinese community, even at election time.

Many people of Chinese ethnicity do not vote, she said.

In between running the lunch club, and a cooking class every other Wednesday, Ms Vigo’s time is mostly taken up helping people with their benefits or medical appointments.

She said she submitted one elderly lady’s pension credit application two months ago.

“Every time we phone they say that they are overloaded with applications,” Ms Vigo said.

“So she is just waiting. Because her husband passed away, she had to apply in her own name. She has no benefit apart from state pension. So she's still waiting for her pension credit to come through and it's been two months.”

Ms Vigo was born in mainland China, but her mother was originally from Hong Kong and she later lived and worked on the island.

Unlike many of her compatriots, she moved here with her husband rather than joining family members in Northern Ireland.

“When I first came here, I was told to be careful because they (the Chinese community) are related to each other,” she said.

“So be careful what you say to anyone, otherwise you can offend the whole village without knowing!”

Luke Butterly is a freelance journalist in Belfast

By

By